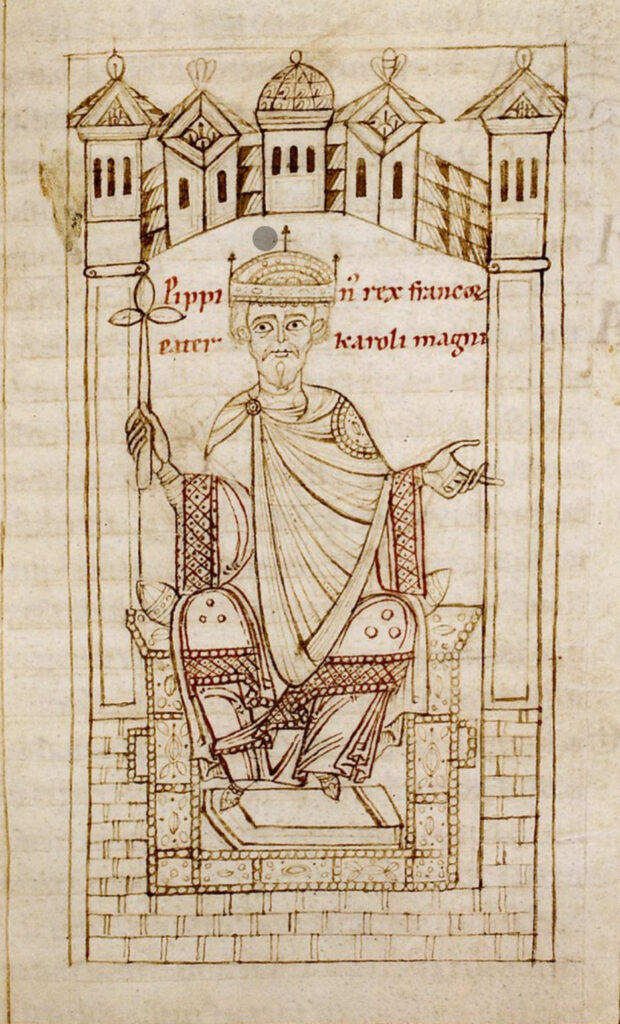

Pepin the Short & Charlemagne

What we now call “Gregorian chant” began with a political alliance between Pepin the Short and Pope Stephen II. In exchange for protection against the invading Lombards, Pope Stephen II declared Pepin the Short as ruler of the Franks.1 His son, Charlemagne, used liturgy to unify the kingdom and imported Roman cantors to Gaul.2 There, a Frankish-Roman hybrid (Gallican + Old Roman chants), or “Gregorian chant” was created.3

Written Notation

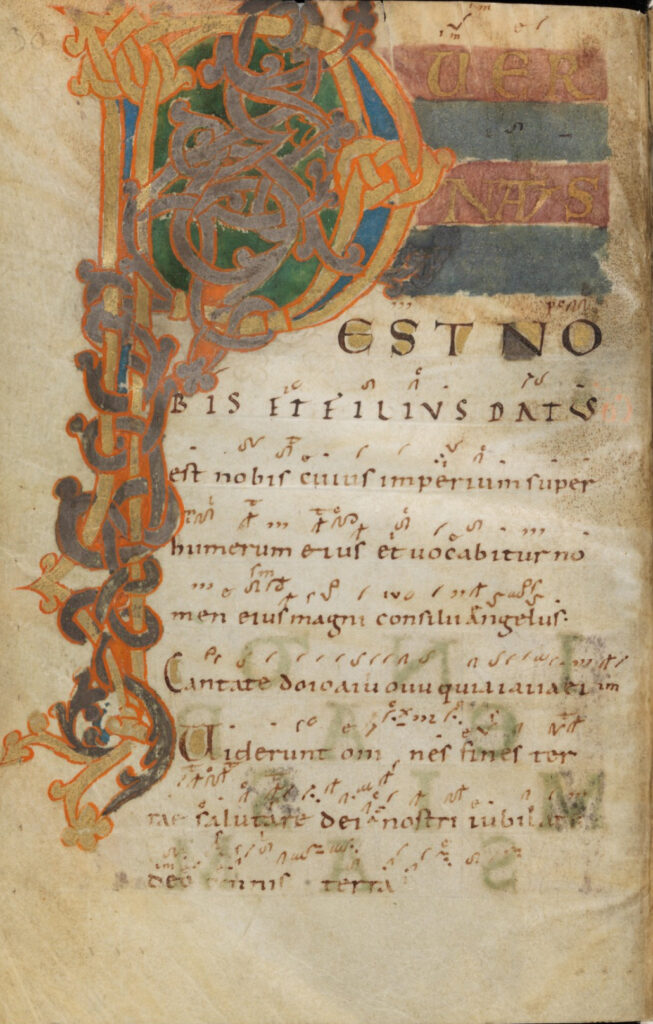

For about five generations, Gregorian chant was a common oral tradition, as shown by the amazing concordances in the later manuscripts. Although the earliest written records appeared in the eighth century, adiastemetic neumes (squiggles that lack precise pitch indications) only later emerged around the tenth century. The neumes, deriving from diacritical signs, underscore the inseparable marriage bond between the sacred text and the melody.4 Thus, the sacred text becomes the point of departure for interpretation. With the advent of notation, rhythmic nuance began to decline.

Gregorian semiology returns to these primary sources to better interpret the rhythmic integrity of the text. It involves the confluence of musicology, theology, and performance practice. There are two primary notational schools: St. Gall and Laon. This website will cover St. Gall notation and reference Laon where needed.

Dom Cardine

The monastery of Solesmes, established in the 19th century, spearheaded the Gregorian chant revival within the Roman Catholic Church. Chant manuscripts across Europe were scrutinized and copied into facsimiles – cutting-edge technology at the time. The Graduale Romanum, published in 1907 was partially based on this paleographic research.5 After its publication, Dom Mocquereau – better known for his didactic “Solesmes Method” – still continued paleographic research. Dom Cardine followed in Mocquerau’s footsteps and founded Gregorian semiology based on the adiastemetic neumes found in manuscripts from the 9th-11th centuries. When the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music needed a paleographer, Solesmes sent him on the principle of “promoveatur et amoveatur”. From 1952 until 1984, he taught, refined his theories, and educated the next generation of semiologists.6

- Richard Taruskin. “Chapter 1 The Curtain Goes Up.” In Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century, Oxford University Press. (New York, USA, n.d.). Retrieved 20 Apr. 2024, from https://www-oxfordwesternmusic-com.proxy123.nclive.org/view/Volume1/actrade-9780195384819-div1-001002.xml ↩︎

- Richard Taruskin. “Chapter 1 The Curtain Goes Up.” In Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century, Oxford University Press. (New York, USA, n.d.). Retrieved 20 Apr. 2024, from https://www-oxfordwesternmusic-com.proxy123.nclive.org/view/Volume1/actrade-9780195384819-div1-001004.xml ↩︎

- Ruff, Anthony, OSB. “Using Inherited Genres: I: Gregorian Chant.” In Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform. (Chicago, USA, 2007). ↩︎

- Ruff, Anthony, OSB. “Using Inherited Genres: I: Gregorian Chant.” In Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform. (Chicago, USA, 2007). ↩︎

- Ruff, Anthony, OSB. “The Nineteenth-Century Gregorian Chant Revival.” In Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform. (Chicago, USA, 2007). ↩︎

- Professor Godehard Joppich, interviewed by Stephen Concordia, OSB. January 1, 2005, Frankfurt, Germany. Private interview transcription approved by Joppich and sent by the interviewer to me on December 15, 2020. ↩︎